Thursday, December 10, 2020 Our America by Zanaya Hussain

“Buffalo is often called the City of Good Neighbors because it is a city that’s home to a large refugee and immigrant population. As Buffalonians, we pride ourselves on this flourishing diversity. But with xenophobia and hate crimes on the rise, sometimes the message behind being a City of Good Neighbors is forgotten. Through this summer fellowship at the Just Buffalo Writing Center, I interviewed three different immigrants who call America home, and offer readers a snapshot of their lives. My hope is that, by sharing these narratives, we can learn how each of our experiences intertwine and how human empathy ties people from varying backgrounds together. These profiles act as a response to the question, What makes being the City of Good Neighbors so wonderful?”

“Buffalo is often called the City of Good Neighbors because it is a city that’s home to a large refugee and immigrant population. As Buffalonians, we pride ourselves on this flourishing diversity. But with xenophobia and hate crimes on the rise, sometimes the message behind being a City of Good Neighbors is forgotten. Through this summer fellowship at the Just Buffalo Writing Center, I interviewed three different immigrants who call America home, and offer readers a snapshot of their lives. My hope is that, by sharing these narratives, we can learn how each of our experiences intertwine and how human empathy ties people from varying backgrounds together. These profiles act as a response to the question, What makes being the City of Good Neighbors so wonderful?”

Zanaya Hussain was a 2020 Just Buffalo Writing Center Fellow. She currently attends the University at Buffalo as a Social Science major with a concentration in International Studies. Zanaya is a writer and spoken word artist. She forever writes in an attempt to express the indescribable.

“You can be anything. If you work hard you can achieve.”

—J.

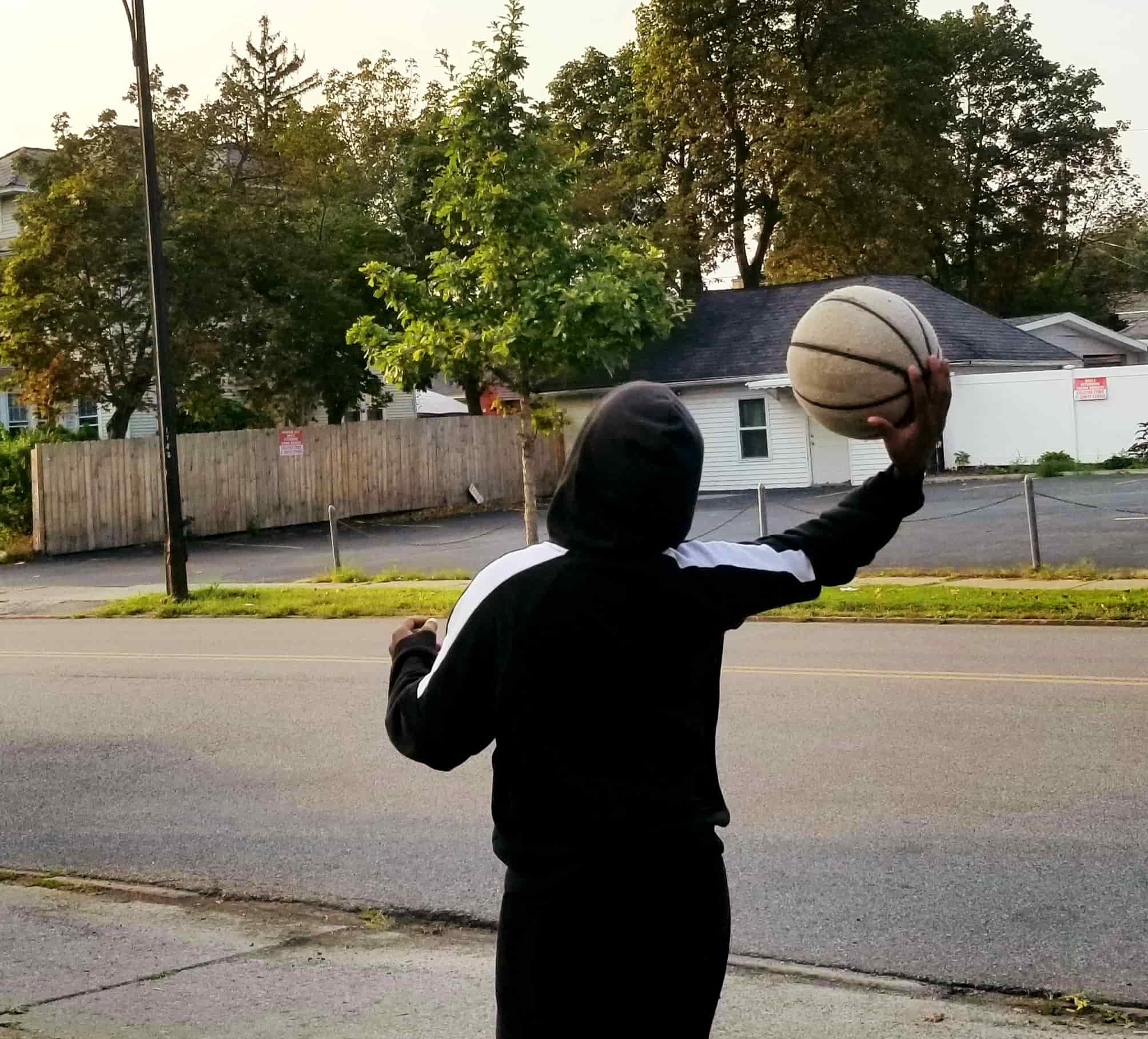

Photo Credit: Zanaya Hussain

When hearing the bounce of a basketball and the swish of a net or the wheels of a skateboard gliding through the street, the neighborhood knows J is around. He greets us with a smile and asks us if we want to play outside. Three houses down lives a 15-year-old basketball player, musician, big brother, and friend. J is outgoing, bold, and light-hearted. He approaches life courageously, talking to anyone he finds interesting and picking up new hobbies, like badminton and guitar.

J was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, spent three years in Tanzania, moved to Kenya and spent seven years there before finally coming to America at the age of 10. J spent time in three different states before finally settling in Buffalo, NY. When asked why he moved from state to state, J responded simply, “Life was kind of tough, but it was fine.” Not every environment was a good fit for J’s family. His father didn’t have access to a car and was forced to bike everywhere, so during the winter it was a challenge to go places like the supermarket or the bus stop. However, J never personally felt burdened. He exclaims that he owned, “two bikes, two soccerballs, a downstairs and upstairs, a TV, everything that [they] needed. But [his] dad didn’t have a good job.”

Eventually J’s grandpa in Buffalo called and “welcomed [the family] here,” so J’s parents decided to take a chance and move to Buffalo. It can be painstaking to find all the factors of stability within one place; constant relocation is a universal part of the refugee experience.

When asked about his feelings towards Kenya, J immediately explains how much he misses the country that he once called home. “Here too I got friends, but [in Kenya] I got friends, and family too. So I miss it.” J wishes he could visit Kenya, and remains hopeful that one day his family might return. Once his parents receive citizenship, J believes they will be able to travel more freely and go back to the stops they made on their journey here, like Kenya and Tanzania. Refugees must live in the U.S. for at least five years before they can apply to become citizens, and for J’s family, 2020 is the year they will be eligible. But despite the nostalgia he feels towards Kenya, J is glad he can call America home too. “We actually would have went to Australia but we missed one interview — boom everything changed.” When I questioned J about whether he would have preferred Australia to America, he compared the two by saying, “Australia is like back in Africa,” specifically with the climates of both continents.

Legally, J is a refugee but in his own mind that is not how he identifies himself. “I knew I was a refugee, it just sometimes goes over my head.” The reason he so easily forgets is because of J’s own implicit biases about what makes a refugee. “I had a nice house, it was made out of bricks, my dad worked on it. I had nice neighbors,” recalls J when he thinks back to his childhood in the DRC and Kenya. His family is adjusting well as refugees in America but J is having a harder time. He doesn’t like the constant moving around because every place he emigrates, he leaves behind “a nice house” and “good friends that help [him].” One way for J to cope with his frustration is through humor and friendship. “We make jokes about everything. We don’t have to fight.” J feels extremely welcome at his current school, International Preparatory School and within the Buffalo community.

J notes that school in the U.S. is very different from school in Kenya. In the United States, emphasis is placed on English, math, and the sciences. Back in Kenya, J’s school made learning English and Swahili a priority. This is why J is fluent in nearly three different languages.

In American schools, J describes a lack of independence among the students. “[Here] in 8th grade we used to line up, go as a class. It sucks.” J was happy to find that ninth graders were trusted to switch classes all on their own. In Kenya, there was no switching classes. “We only stay in one class…but different teachers.” J was taught by the same teacher all throughout his elementary years. He had one teacher who taught different subjects. J went to a “public school” with “a lot of kids.” But a large class size is something J enjoys. “It was actually good cause [during] recess [we] play soccer or did something dumb or stupid. We just used to take a scarf and just start beating each other. The spanks are really hard,” J adds with a wincing smile.

The transition to an American school system took some time for J. “When I was here I started to get really mad.” In many of the schools he attended in America, J would be blamed for things he didn’t take part in, like fights. This angered J and encouraged him to fit the narrative others were dictating for him. “I started to get in a lot of trouble.” J recounts his middle school years explaining, “This one time I fought a student and then a teacher stepped in and I started fighting her.” J received suspension and in-school suspension multiple times each year: “Then in 7th grade I let this one girl beat me. I didn’t even touch her but I got suspended for it.” When J tried to come back to school during his suspension his school found out and placed him in ISS (in-school suspension). J reflects on his troubled years, “I used to get mad easily, I couldn’t control it at that time. But as I started to get older, I started to understand things and be less angry. I started to think before I do.”

Photo Credit: Zanaya Hussain

J still doesn’t feel like he fully fits within his school, his home, or in this country. The pressure from his parents, teachers, and from society weighs heavily on him. His eldest two siblings are still living in Kenya, so here in America J is the eldest brother to his younger sisters. He plays a big role in keeping his family afloat. “My dad knew a little English, I knew more than him so I actually helped most of the time.” When J’s parents leave he becomes the guardian of his little sisters. “Babysitting,” he says “sucks.” While his parents hope to buy a house soon and move out of their tiny apartment, as of right now his home is always loud and busy so he spends all of his moments of free time outside. “I go outside to take a break.” Within his family he takes a large responsibility for their wellbeing which contrasts the belittlement he feels outside of his home within institutions.

Another way J takes a break is when he goes to church. Back in Kenya, J’s family had a very close relationship with their local church. His father, who is a singer and guitarist, like J, released his first album with the help of their church choir. Maintaining this close relationship to religion allows J to feel connected to Kenya and the DRC. In Buffalo, he and his family attend a small church. There, J plays the drums and also sings in the choir.

As far as his plans for the future? J is in no hurry to decide. He wants to use his knowledge and skills to benefit others but doesn’t want to think too far into the future. Right now he prefers to focus on mastering new songs on the drums and improving his guitar-playing skills. When J isn’t showcasing his musical talent, he is playing sports. His favorite sport is soccer. Recently J was thinking about learning to code through his school in order to design a video game, “I can make [a video game] my way.” J thrives on freedom and creativity. He adds his own flair to everything he does, whether it’s a new dunking trick, a song he wrote on the guitar, or possibly in a video game he will code.

J plans to go back to the Democratic Republic of Congo some day. He doesn’t know what he wants to be when he grows up, but figures a career in public service in the DRC will allow him to have a more direct impact. “I need to go back there, teach them the things that I know and then they will help other children too, to achieve the things they want.”

“You can choose freedom. You can choose to work. You can choose to collaborate with other humans. But you have to be brave enough to do it.”

—Nada Odeh

I have known Nada for roughly 4 years through the Buffalo Summer Symposium, also known as the Summer Academy for Human Rights, held annually at Erie 1 Boces. This year the seminar was held virtually, like most other events, but needless to say Nada was online with our group offering her charisma and talent as if she were with us in person. Every year since 2016 at the symposium, Nada has dedicated a session to painting; to turning art into activism. Nada has utilized art as a tool in creating change in her home country, Syria, and in her second home, America.

Nada first received her B.A. in Fine Arts at Damascus University. In 2012, Nada left Syria to spend time in Dubai and the United Emirates. In 2013, she came to America and began pursuing a M.A. in Museum Studies at Syracuse University through a scholarship program known as 100 Syrian Women 10,000 Lives. 100 Syrian Women 10,000 Lives is a scholarship awarded to Syrian women who take civic responsibility and demonstrate both leadership and academic excellence. Nada received this achievement and was able to successfully graduate in 2018 from her masters program at SU. Although she started off with small roots, she now thrives as a renowned artist, with her artwork having been exhibited in Damascus; Dubai, United Arab Emirates; New York City; Detroit; Toledo; Tiffin; Washington D.C.; Syracuse; Albany, New York; and Auburn, New York.

Nada’s relationship with art began developing as a young child, through the influence of her mother, which makes art one of her strongest tools in building awareness around the Syrian refugee crisis. She has been drawing since the age of three. She explains that her “mother was an artist herself. She was not really a practicing artist. She took classes for several years under professional teachers and artists in Syria during the 1950s. [My mother] was my very first art teacher.” While Nada watched her mother paint and create with pencils, acrylics, and watercolor she realized she, too, wanted to have an artist’s eye. “[My mother] saw that I have all this passion for art. She wanted to strengthen my performance as an artist.” This is why all throughout the summers of elementary and middle school Nada was registered in art classes. “I spent my whole summers painting and drawing.” Art became a pivotal outlet for Nada to cope with hardships. Art is the trusted companion that aids Nada in surviving.

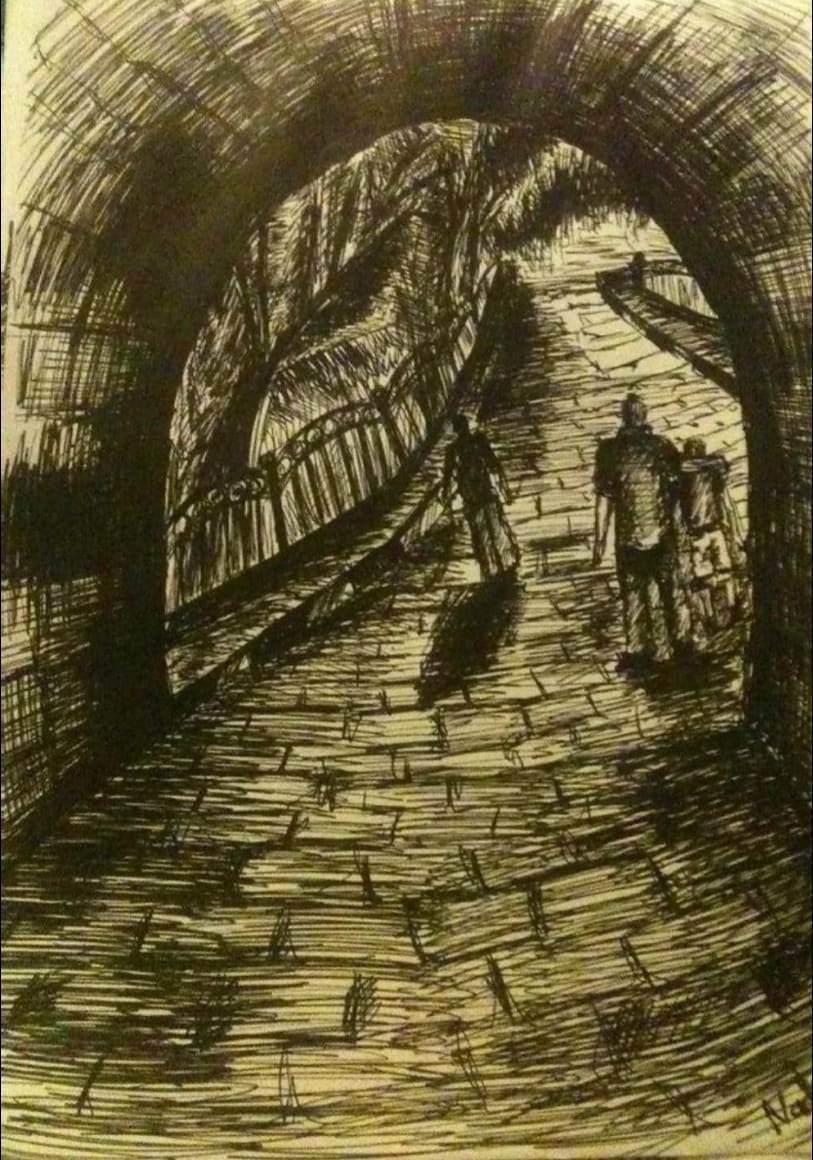

“Damascus the castle”

Born in Syria, Nada is a survivor of the Syrian refugee crisis and is now an asylum-seeker in America. She never imagined leaving the beautiful city of Damascus, and still has a strong attachment to her home-country. “I didn’t leave Syria by choice. I left it by force…Every time I close my eyes I always see myself walking in the streets of Damascus. Those memories are a part of me not wanting to feel separated from home.”

Nada is part of what she calls the “the New Syrians,” the Syrians who didn’t come to America 30 years earlier in search of prosperity, but rather the Syrians who are looking for sanctuary. “Older immigrants do not understand what we go through. Coming after the war is totally different than leaving your country and knowing that you are able to go back whenever you want, [it] makes you more able to achieve things.” New Syrians don’t have the luxury of stability or choice so even when migrating to a new country they oftentimes face mental adversity.

The war, the Syrian regime, and simply needing a safer place for her children, forced Nada to make the difficult decision to flee. Before Nada graduated from college she had multiple engagement offers from Syrian men in America, but always declined because she didn’t want to ever be too far from her home in Syria. To this day it still dawns upon Nada that she may never visit her home again.

Nada’s heart may always be in Syria, but she’s worked hard during the last seven years to embrace her new life in America and use her art as a way to communicate the refugee experience. Images of refugee camps and the pivotal experiences which make up her journey can be seen in her artwork. In her art series titled, Royalty in Refugee Camps, Nada reflects on the idea that refugees have pride and value in their home country, but when they have to resettle in a new country where their worth isn’t immediately recognized, it shakes their confidence. This phenomenon is seen in many countries across the globe. Refugees are often pitied and seen as powerless. When collecting donations for a refugee camp in Turkey Nada noted, “people were not respecting refugees” and were sending donations in extremely bad condition.

Recognizing this lack of empathy and consideration pushed Nada to take back power and create the Royalty in Refugee Camps art series. “I wanted to reflect the whole experience in a different way and not show the refugees as being very miserable people but as a person in their house.” Nada showcases the individual without the label of refugee. Depicting the strong sense of self they had in their home and contrasting that with the background of a refugee camp illustrates that the experiences of a refugee does not define them.

“I am a princess”

Labels can be restricting and place expectations on people. Nada’s artistic vision is continually adapting. Thus, through her art, Nada strives to break the boundaries that label us, and to teach others that humans and the life they make up cannot be shoved into boxes. Nada fights for this message through her art and through her work as an activist. America means a lot of things to Nada. It’s a place of stability for both her and her children, but, most importantly, America is now home. This is why Nada continues to act as an advocate and defender for the silenced voices in America and further works to amplify these voices. Nada doesn’t want to cap herself by only supporting other Syrian refugees and asylum seekers, but rather be open-minded and step out of the bubble of her own life.

One way she recommends doing this is by volunteering, “People under appreciate volunteering, but volunteering is a great way to be part of the community ⎼ to be able to mingle in the community.” Volunteering is a way Nada integrates into her local community and into American culture. Through volunteering she can meet new people from completely different walks of life and learn their struggles. Volunteering has forced Nada out of her comfort zone but has also enabled her to distinguish how she can better her current community, and her country America, as a whole. She is a strong ally in both the Black Lives Matter movement and the Women’s Rights movement. “You’re either a humanitarian or you are not. You can’t say I’m a humanitarian only for the Syrian crisis but then forget about other issues. I think it’s all connected.” This intersectionality in systemic prejudice, that Nada identifies, is key in constructing a more equitable society. Nada not only upholds Syrian rights but all human rights. She doesn’t want to feel limited in how she can help.

“I am Syria”

Nada tells me that she is changing everyday, that she always seems like a new person. “I change a lot. I don’t know why, I look always different. I’ll never find one photo of me that looks like the other. Sometimes I think this is a different person but the reality is, it’s me. Maybe I should have gone into acting.” This fluidity that Nada has in never tying herself to one identity allows her to so deeply empathize with people from all types of backgrounds through her art. Instead of letting past experiences and present labels tell her who she is, she sheds any definition. When looking into Nada’s art we look into her eyes to see resiliency of the human spirit. Despite the circumstances a person comes with, if they continue to fight for what they believe in, they will always prevail.

“Our lives are influenced by sacrifices, our sacrifices impact others.”

—Hawo Sadik

Her name is Hawo Hussein Sadik Mabruk Enow Shangalow. Each name is taken from the generation of a father, carrying the names of Hawo’s ancestors. This constant reminder of her roots tethers Hawo to the endless sacrifices her parents have made and to their experiences outside of America. These sentiments combine to allow her to maintain an optimistic perspective in times of alienation or struggle. This positive outlook has enabled Hawo to inspire her younger siblings and other Somali Bantu Bantu girls in her community.

Her name is Hawo Hussein Sadik Mabruk Enow Shangalow. Each name is taken from the generation of a father, carrying the names of Hawo’s ancestors. This constant reminder of her roots tethers Hawo to the endless sacrifices her parents have made and to their experiences outside of America. These sentiments combine to allow her to maintain an optimistic perspective in times of alienation or struggle. This positive outlook has enabled Hawo to inspire her younger siblings and other Somali Bantu Bantu girls in her community.

Hawo’s home-life has taught her that love is care. Her parents’ lives revolve around their children and this can be seen in their decision to uproot themselves from their home country of Somalia, all to create a better life in America. Her parents never saw themselves fleeing as they were so integrated into the vibrant and sunny life found in their community. Hawo’s parents cherished everything about their community, the first time they crossed paths was even at a local supermarket.

“My mom was working in a market and my dad was a translator and tradesmen, so he was able to travel to different countries around Africa. When he [Hawo’s father, Hussein,] was finally on his way home, in Somalia, he stopped at the market.” Hawo begins to chuckle, “and I guess he was mesmerized or whatever.” Hawo concludes that after seeing and learning about Hawo’s mother, Owliya, her father immediately met Owliya’s parents, and he spared no time in making the first move. After learning how much her parents approved of Hussein, Owliya made a decision. Hawo believes the story ends with her mom telling her grandmother, “You know what mom, I’m gonna do this just for you, just to make you happy,” and so Hawo’s mom agreed to get to know her father and decidedly fell in love. Hawo inherited the same filial piety and devotion towards family that her mother possesses.

This attachment to family made it incredibly difficult for Hawo’s mom to uproot herself from Somalia and leave the sanctuary that her family offered, but ultimately she and Hawo’s father decided it was the best decision for their own brewing family. Corruption and violence knocked on every village doorstep and swept Hawo and her family to a refugee camp in Kenya. At two years old, Hawo’s family was resettled in Columbia, South Carolina in the United States with the help a sponsor. Ten years later, her family moved to Buffalo, but they still keep in in contact with their sponsor.

A sponsor, Hawo explains, is a person from the destination country that is entrusted to teach, “new customs to the refugee family and help them to assimilate into life within a brand new country. They assist refugee families in learning the local language and in looking for a job.” If a refugee’s sponsor isn’t already a relative, often they become as close as family and a lifelong relationship is established.

As the eldest daughter and an English speaker for her parents, Hawo was forced to grow up fast. This meant babysitting, filling out paperwork, making appointments, and filling the gaps where her parents couldn’t in a western country; but even after sacrificing her own childhood so that her younger siblings and parents could be more at ease, she remains grateful. Hawo exclaims, “I’m trying my best to make my parents proud and make them feel like it was worth it — to leave their homeland.” From Hawo’s perspective it was worth it to leave Somalia behind, although she acknowledges that, because she was so young, there wasn’t much for her to leave behind.

Coming to a new country as an adult, as Hawo’s parents did, can definitely take a toll on one’s pride. Hawo recounts learning the basics of daily American life like the language and customs, while her parents took much longer to grasp these concepts. She imagines how this shift in power dynamic between child and parent can hurt a mother or father’s pride. Hawo “would have to step-up and translate when…in a supermarket or when in a parent-teacher conference or anything of that nature,” because her parents were not at the level of understanding yet. Hawo infers, “this is something a lot of immigrant children can relate to.” Hawo, and many other child immigrants, possess the self-reliance of an adult. While learning to be more responsible “has prepared us (child-immigrants) to be adults, at the same time it has stripped us of our childhood.”

Coming to a new country as an adult, as Hawo’s parents did, can definitely take a toll on one’s pride. Hawo recounts learning the basics of daily American life like the language and customs, while her parents took much longer to grasp these concepts. She imagines how this shift in power dynamic between child and parent can hurt a mother or father’s pride. Hawo “would have to step-up and translate when…in a supermarket or when in a parent-teacher conference or anything of that nature,” because her parents were not at the level of understanding yet. Hawo infers, “this is something a lot of immigrant children can relate to.” Hawo, and many other child immigrants, possess the self-reliance of an adult. While learning to be more responsible “has prepared us (child-immigrants) to be adults, at the same time it has stripped us of our childhood.”

Hawo advises other child-immigrants and first-generations “to think about the bigger picture.” Additionally she suggests, “maintaining an optimistic view about life” because “it will help you to remain sane.”

Hawo yearns to visit Somalia some day to reconnect with her home country and the identity that comes with it. However, that may be challenging. Somalians have tried to visit or go back, but because of Somalia’s civil unrest and immense corruption, many are prevented. This reality greatly influences Hawo’s goal to return to her homeland, open up a clinic, distribute clean water, and provide humanitarian aid. Hawo believes that “Somalia needs to heal,” and so she hopes she can bring her goal to fruition, specifically in getting more accessible clean water to Somalians because, as Hawo puts it, “clean water is a vital part of living.”

Many of Hawo’s long-term goals lead back to uplifting her family in America and her people back in Somalia. This comes from Hawo’s incisive recognition of her parents’ difficult and ongoing journey. She still ponders what her life might look like if her parents stayed in Somalia; in the end, she’s grateful they didn’t. Hawo is reflective when saying, “I am very appreciative that my parents left their country, a place they’re used to, just for the sake of their children and their futures. I am very, very, very humbled by that.”

“Your parents made a sacrifice by bringing you to a country that they are foreign to, this is a new change for them too. Be patient with your parents, even if you think they’re being unfair. They always have your best interests at heart, they only want what’s good for you.” Hawo’s maturity can be heard with her every word. Hawo is aware that although her parents left an “oppressive country,” it’s still important to be “forgiving and understanding because they are in a country now that is still oppressive,” just in different ways.

“There are a lot of social issues that still haven’t been tackled here in America, so even though you’re supposed to have a better life here that’s not necessarily what’s gonna happen. That’s just what life in America is.” Even after understanding the unjust nature of American society, Hawo believes eventually America will become more equitable in her lifetime, but “in order for that to happen we need to be more understanding of one another, so even as immigrants who get a lot of hate…try to be optimistic to then help others coming after.” Hawo takes on the burden of being an immigrant in America and strives to create equality by understanding and helping others, so that eventually society will become more accepting to new immigrants and refugees looking for homes.

Having reached this middle ground of what it means to be an immigrant and what it means to be an American, Hawo offers a unique take on what America encompasses. Hawo admits that “America is the land of opportunity, but there’s a hidden message in there — the fine print that no one reads,” stating that one must make up a certain demographic “to be eligible for opportunity.” While Hawo agrees that it’s possible for people to become successful in America, some groups of people do have to work much harder. “America is a country of ‘can’ not ‘will’,” Hawo succinctly concludes.

Being a Somali BantuBantu muslimah immigrant has never felt limiting to Hawo, as long as she remembers the sacrifices of her parents and how she will honor these sacrifices. This can render into a heaping amount of pressure to succeed, but Hawo takes this in stride. From her eyes to her voice, Hawo exudes self-confidence.

This belief in herself can be seen in the goals Hawo has set for herself. Hawo will be attending Cornell University in the fall of 2020 as a Chemistry a Chemistry major, as she plans to pursue pharmacology. This summer she spent her days taking chemistry classes through her university, and after struggling in the first few weeks she finally received an A on her last test. On top of summer classes Hawo has been working at her local grocery store, doing henna designs for small tips, and memorizing the Quran. Hawo is incredibly passionate about the things that matter to her and she has big dreams. Sometimes she considers that one day she might have a family of her own, but doesn’t ever intend to give up her career. “Women are capable of doing both,” and so she hopes her parents can begin to see how strong of a daughter they raised.